Over the last 30 years the mass migration of rural villagers has not only enabled the growth of Chinese cities but has had an equally dramatic effect on their rural homeland. The rural is undergoing dramatic economic, social and physical changes that will only accelerate as China prepares to further urbanize half of its remaining 700 million rural citizens over the next 30 years. These changes are being accompanied by a transformation in the vernacular architecture of China: a wholesale shift from regionally specific building types to generic, concrete, brick and tiled buildings. Within this scenario of potentially extreme changes to the social and built landscape, the architect is wholly absent. Indeed, the most relevant question for the profession is: what can an architect do in a context where architecture is deemed unnecessary?

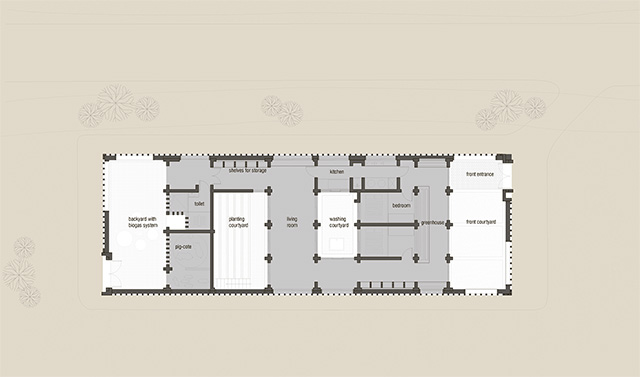

Shijia Village is located in the northern province of Shaanxi, near the city of Xi’an. The project was funded by the Luke Him Sau Charitable Trust with support from the Shaanxi Women’s Federation and The University of Hong Kong. The authors’ project there looks at the idea of the vernacular village house and attempts to propose a contemporary prototype. Initially it began as an experiential learning workshop with students from The University of Hong Kong. All the houses in Shijia Village are originally of mud brick construction and occupy parcels of the same configuration: 10 m x 30 m. The houses are each in the midst of a long process of change as villagers gradually renovate and build upon the courtyard typology, traditional elements fused with new brick and concrete buildings. Apart from the identically defined parcel boundary, no two houses are alike. Students documented and interviewed various families in the village, collectively compiling a portrait of the modern Chinese village house: a portrait not only of building types but of a lifestyle in transition.

Perhaps no aspect of this portrait is as relevant as the rise of the village contractor. As the houses transform from mud brick to concrete and tile, the construction process itself has been radically altered. As most able-bodied villagers have left to work in cities, the hiring of outside labor and materials has replaced collective self-construction, thus making the physical transformation of the village a symptom of a larger shift from economic self-reliance into a system of dependency, threatening the very concept of a rural livelihood.

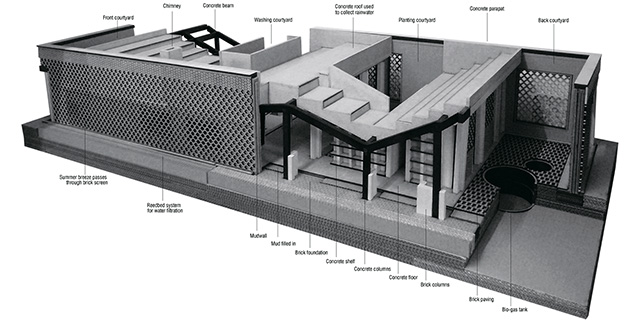

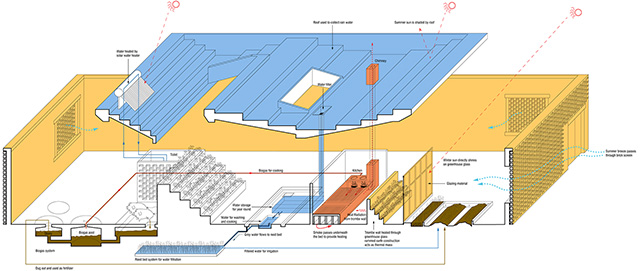

In the Chinese context, rural livelihood is perhaps best expressed through the utilization of the domestic courtyard, where much of life takes place. Indeed, the majority of a village’s open space is contained within the walls of the house. This sets up an intimate relationship between the courtyard and other interior rooms that is both visual and functional. An architects’ prototype house design includes four functional courtyards as the primary elements of the house. The courtyards are inserted throughout the house to relate to the main functional rooms: kitchen, bathroom, living room, bedrooms. In addition each courtyard is spatially unique. One could say the house is designed around the courtyards.

One of the main intentions of the prototype house is to resist the villagers’ increasing dependency on outside goods and services. The roof is multifunctional, providing a space for drying food, steps for seating and, in the rainy season, a means to collect and store rainwater so that it can be used during the long and dry summers. The house becomes an example of self-reliance. The courtyards house pigs and an underground biogas system produces energy for cooking. Smoke from the stove is channeled through the traditional kang or heated bed before it exits the chimney.

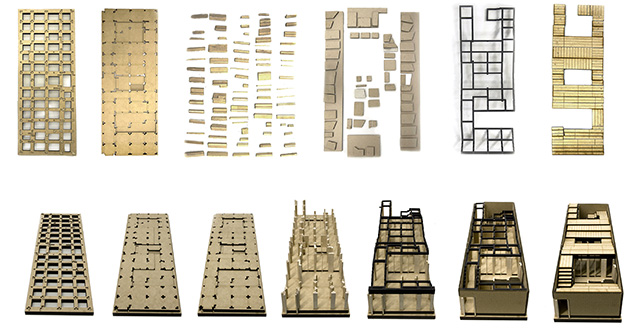

The structure of the house brings together old and new. A concrete column and roof structure is combined with mud brick infill walls ? mud brick being a traditional means of insulation in the continental climate. Unlike the traditional mud structure, however, the new hybrid satisfies criteria for earthquake resistance. The entire outside wall of the house is wrapped in a brick screen. This not only serves to protect the mud walls, but also shades windows and openings. By combining vernacular ideas from other regions of China as well as traditional and new technologies, the design is a prototype for a modern Chinese mud brick courtyard house. Currently, the process of rural development increasingly favors the destruction and abandonment of the traditional in favor of the new. The Shijia Village Houses attempt to bridge between the two extremes and preserve the intelligence of local materials and techniques. However the project is not simply a traditional courtyard house. It is a result of investigation into the modern village vernacular and represents an architectural attempt to consciously evolve vernacular house construction in China.

PROJECT DATA:

Title: A House For All Seasons

Location: Shijia Village, Shaanxi Province, China

Designer: John Lin / The University of Hong Kong

Commisioning donor: Luke Him Sau Charitable Trust

Project collaborators: Shaanxi Province Women’s Federation, Qiaonan Town Government, Shijia Village Government, The University of Hong Kong

Credits: Huang Zhiyun, Kwan Kwok Ying, Maggie Ma, Jane Zhang, Qian Kun, Katja Lam, Li Bin

Date: March 2012

Size: 380m2

Cost: 53,400 USD

Unit Cost: 140 USD/m2